Listen to the audio version of this article. Duration: 12 minutes.

Throughout his career, Gaetano Pesce challenged conventions in both art and design. By embracing imperfection and individuality, he crafted pieces that provoked thought and emotion. His iconic works, like the Up Series chairs, confronted societal norms, while his architectural projects showcased his deep connection to the environment and commitment to innovative materials.

Gaetano Pesce was never one for conformity. Born in La Spezia, Italy, Pesce spent his life merrily rejecting straight lines, literal thinking, and anything resembling conformity. His body of work, spanning over half a century, can be seen as design with a playful wink, bending the rules and reshaping them into something unexpected, vibrant, and full of life. Whether through furniture with a face or buildings that sprout greenery like they’re fed on laughter, Pesce was more than just a designer, he was a provocateur, an anarchist in the world of chairs and concrete, and ultimately, a storyteller who used resin, foam, and wit as his narrative tools.

Born to bend, and break, the rules

Pesce was born in 1939, as Italy and the rest of the world entered a period of profound upheaval. In the aftermath of the war, while others focused on rebuilding, Pesce questioned why things were built that way to begin with. He studied architecture at the University of Venice, where he found himself in an intellectual pressure cooker of radical ideas, surrounded by thinkers who viewed tradition the way Pesce would later view a straight-backed chair: with irrepressible suspicion. Venice, with its labyrinthine waterways and crumbling, timeless architecture, provided a perfect backdrop for Pesce’s earliest experiments, whether in art, architecture, or ruffling the feathers of the design establishment.

“We are supposed to be free, and to be free means to be incoherent”

Sitting pretty? Not as long as he had a say.

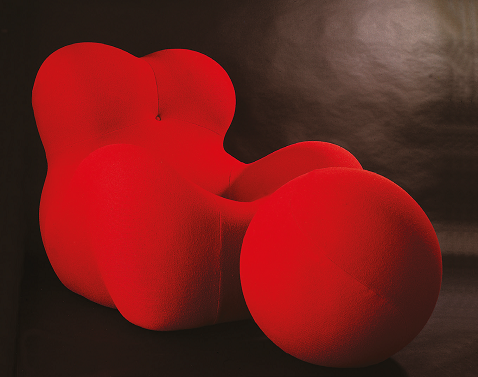

If you were expecting a polite, ergonomic chair that discreetly supports your lumbar region, Pesce’s designs were not for you. His most famous creation, the Up Series, particularly the Up 5 & 6, wasn’t just a chair; it was a manifesto posing as furniture. Debuting in 1969, the piece was shaped like a woman: voluptuous, suggestive, and chained to a ball, a biting comment on women’s societal roles, delivered with a flourish of foam and irony. Pesce’s cheeky design turned heads and likely raised a few eyebrows at polite dinner parties. The fact that the chair came vacuum-packed and expanded into its full form once freed from its constraints felt like one big metaphor wrapped in polyurethane.

The Up 5, also known as the Donna chair, wasn’t just a chair you sat in. For Pesce, design had to mean something. He wasn’t in it to make pretty things, and he certainly wasn’t here for comfort. The Donna chair asked its owners a question: Are you free, or are you sitting in the same trap as this chair’s captive form?

“The first freedom to reach is from ourselves”

The joy of unreliable materials

While other designers leaned on classic materials such as leather, wood or the occasional exotic metal, Pesce had other plans. He was less interested in steel and structure and more fascinated by rubber, foam, and most notably, resin, which he handled with the enthusiasm and spontaneity of a child playing with newfound toys.

Resin, as it turned out, was the perfect medium for Pesce’s ethos: it was versatile, unpredictable, and it rarely behaved. Much like Pesce. When he crafted pieces like the Resin Chairs of the 1970s, the results were as much a surprise to him as they were to the audience. Each piece was distinct - a controlled accident - with colours blending and hardening into forms that no factory assembly line could ever replicate. For Pesce, this was key. Every chair, every object was an individual, much like the people he designed for. His work mocked the very idea of mass production, yet used industrial processes to create singular, unrepeatable works.

The same irreverent sense of material play led to one of his more whimsical creations, the Moloch lamp, a giant, oversized desk lamp. At more than 180 centimetres tall, the Moloch lamp took the humble office accessory and turned it into an absurdly oversized presence that somehow managed to be both charming and menacing. A hallmark of Pesce’s ability to blend humour with a hint of danger.

“Design is not just about creating objects. It is about creating meaning”

Pesce’s buildings go organic

Though best known for his furniture, Pesce’s architectural ventures were no less audacious. When tasked with designing a building, he approached the project as if the building itself were alive, growing, shifting, and unapologetically playful.

One of his most audacious architectural experiments was the Rubber House in Brazil, a home that embodied his commitment to experimentation. With a facade made entirely of rubber, the house seemed to breathe and shift, bending and contorting with its surroundings. The Rubber House blurred the line between architecture and sculpture, much like the Organic Building in Osaka, Japan. Completed in 1993, this Osaka landmark wasn’t just a building, it was an environmental statement. Covered in brightly coloured resin and filled with plant life, the structure is part greenhouse, part funhouse. A vibrant rejection of the steel-and-glass boxes sprouting up in cities worldwide.

Beauty in the flawed

While many designers spend their careers pursuing perfection, Pesce actively ran in the opposite direction. For him, the human condition was far too complex, too imperfect, to be represented by sterile, symmetrical objects. He embraced asymmetry, irregularity, and the wonderfully messy process of creation. In his Six Tables on Water series, Pesce’s use of resin mimicked the fluidity and unpredictability of water itself. Each table surface, like an unruly pool, formed its own distinct pattern, making it impossible to replicate. The imperfection wasn’t just tolerated, it was celebrated. Pesce’s work was a finger in the eye of uniformity, a gentle reminder that perfection is overrated and, frankly, kind of boring.

As art historian Glenn Adamson noted in his biography of Pesce, Gaetano Pesce: The Complete Incoherence, “Pesce’s genius lies in his refusal to be consistent. Just when you think you’ve understood his work, he does something to surprise or confound you. His is a design language where incoherence itself becomes a kind of coherent principle.

Radicals and Rebels: MoMA’s 1972 Exhibition

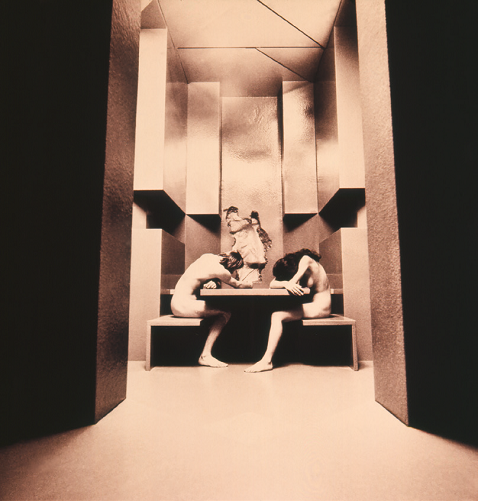

Pesce’s influence wasn’t confined to the pages of design history: his work was a living, breathing critique of contemporary society. This stance earned him a place in MoMA’s landmark 1972 exhibition, Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, where his designs were exhibited alongside other radicals of Italian design. The show, which challenged the then-prevailing ideas of modernism, was a pivotal moment for Pesce. His participation cemented his reputation as one of the leading figures of the Italian Radical Design movement, a group bent on exploring the intersection between design, technology, and society in a rapidly changing world.

Pesce’s contribution was, naturally, far from conventional. His Habitation for Two concept pushed the boundaries of what domestic even meant, offering both playful and critical perspectives on contemporary life. As with much of his work, this work was about more than just functionality, it was about questioning the social and cultural frameworks around the spaces we live in and the objects we live with every day.

Design as a political act

Pesce wasn’t shy about inserting politics into his designs. From the feminist overtones of the Donna chair to his critiques of mass production, Pesce treated design as a platform for protest. He wasn’t afraid to stir the pot, whether it was societal expectations, traditional design, or even his own audience.

For Pesce, every object had the potential to become a vehicle for social commentary. His works were infused with humour, but they also carried serious undertones, addressing everything from environmental issues to human rights. His iconic designs didn’t just occupy space, they sparked conversation, prodded people to think, and in many cases, challenged the very systems they were part of. He rejected the notion that designers should just "solve problems." Instead, he viewed design as a means to question the status quo.

Pesce lives on

Gaetano Pesce passed away in April 2024, but if you think that means he’s gone for good, you’d be wrong. His work continues to laugh, provoke, and question from the galleries and museums that now house his creations. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and countless other institutions proudly display his pieces as part of their permanent collections, and they whisper (sometimes shout) his message: Design should never sit quietly. Pesce’s passing marked the end of an era, but his legacy as a design troublemaker lives on. A new generation of designers continues to take cues from Pesce, daring to experiment, provoke, and above all, have fun. And so, the world of design moves forward, just a little messier, a little more colourful, and a whole lot more interesting for having known Gaetano Pesce.

Bio

Gaetano Pesce (1939 - 2024) was born in La Spezia, Italy, and went on to become one of the most influential figures in contemporary design. He studied architecture at the University of Venice, where his unconventional approach began to take shape. Over his five-decade career, Pesce became known for his use of unconventional materials such as resin, foam, and rubber, and for his playful, thought-provoking works that blurred the lines between art, design, and architecture. His most iconic creation, the Up 5 & 6 (Donna Chair), debuted in 1969 and remains a powerful commentary on gender and social roles. Pesce also made waves with his Organic Building in Osaka, Japan, and his experimental Rubber House in Brazil. His works featured prominently in major exhibitions, including MoMA’s groundbreaking 1972 show Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, which cemented his place in the Italian Radical Design movement. Pesce’s designs are held in prestigious collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Throughout his career, Pesce used design as a platform for social commentary, tackling themes such as feminism, individualism, and environmental awareness, always with a sense of humour and irreverence.

Copyright © Homa 2025

All rights reserved

.jpg?VGhlIFBlcmZlY3QgU2xvdC1pbijmraPnoa4pLmpwZw==)